Cellulosic Biofuels and Biorefineries

Giant King Grass, which is a non-food, non-invasive grass, serves as feedstock for producing liquid biofuels-including cellulosic ethanol, methanol, diesel fuel and green gasoline-for transportation vehicles such as automobiles and trucks. Collectively these liquid transportation fuels are known as "grassoline". During the production process, the cellulose content of Giant King Grass is converted through fermentation, high temperature gasification or other processes into liquid biofuels replacing the need for petroleum. As part of the trend away from using petroleum or food crops as a feedstock, many energy, chemical and other industries that depend on petroleum as a fuel or feedstock are developing capabilities to produce cellulosic biofuels, biochemicals, bio plastics and biomaterials from grass-based biomass and will need large and continual supplies of feedstock.

Biofuels are produced from non-petroleum, non-fossil biomass materials such as agricultural crops (e.g., corn, sugar cane, wheat, rice), seeds and other oil-bearing fruits or plants; grasses; agricultural waste (e.g., corn stalks, wheat and rice husks); commercial or food waste (e.g., cooking oils, wood chips, sawdust); and other "renewable" sources. Using food such as corn for biofuels is very controversial and many countries have limited or banned the use of food products as feedstocks for biofuels. This is led to a search for nonfood alternatives. A good example of a nonfood feedstock is corn straw or stover which is the part of the corn plant that is left after the ears have been picked. Corn is rich in sugar and easily fermented into liquor or ethanol. Corn straw is rich in cellulose which must be converted into sugar and then fermented which adds another step and the resulting ethanol is called cellulosic ethanol. Corn straw is only one example of cellulosic material that can be fermented into ethanol. Biomass can also be gasified using high temperatures and then converted into liquid biofuels. Both of these processes are feasible, and many companies are working very hard to make these processes commercially viable.

However most of these companies are working on the conversion processes and assume that the required biomass will be available in large quantities at reasonable prices. This has not been the experience in China, India or Thailand where biomass is used to generate electricity and heat. The prices have tripled in the last several years and agricultural waste is becoming difficult to obtain in the large and reliable quantities needed. Dedicated energy crops such as Giant King Grass are now viewed as necessary for the success of a large-scale biofuels industry. Giant King Grass has properties nearly identical to corn straw, but has 10 times the mass yield per acre. In addition, in warm areas where Giant King Grass grows well, it can be harvested 12 months a year and one does not have to wait for the food crop to mature before the waste feedstock is available. Because of its high yield, Giant King Grass is usually less expensive than agricultural waste which has to be collected over long distances.

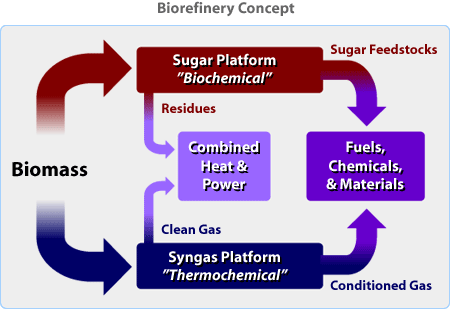

Biofuels are produced in factories called biorefineries which integrate biomass conversion processes and equipment to produce fuels, power, chemicals and bio materials from biomass. According to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) , the biorefinery concept is analogous to today's petroleum refineries, which produce multiple fuels and products from petroleum. Industrial biorefineries have been identified as the most promising route to the creation of a new biobased industry.

National Renewable Energy Laboratory

NREL's biorefinery concept is built on two different "platforms" to promote different product slates. The "sugar platform" is based on biochemical conversion processes and focuses on the fermentation of sugars extracted from biomass feedstocks. The "syngas platform" is based on thermochemical conversion processes and focuses on the gasification of biomass feedstocks and by-products from conversion processes.

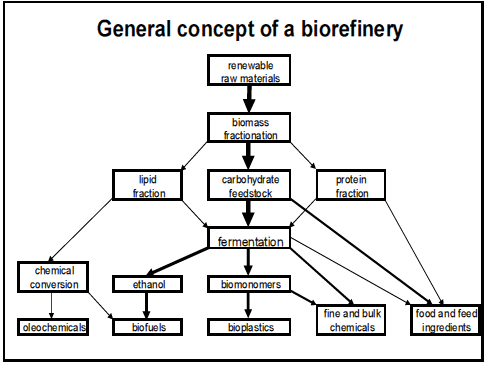

Example of "Biochemical -Sugar Platform", Prof. Wim Soetaert, Univeriteit Gent

High-value chemicals produced in a biorefinery can be used to make plastics, replace nylon, make detergents, antibiotics, cosmetics, sweeteners, flavors and fragrances. Protein can be recovered and used for food and feed ingredients.

Biofuels Overview

The most common feedstocks for today's biofuels vary by country. In the U.S., corn and soybeans are most prevalent; Europe tends to use flaxseed and rapeseed; Brazil, sugarcane; and Asia, palm oil. Brazil introduced ethanol from sugarcane more than 25 years ago. In 2008, biofuels were worth $34.8 billion on the global market.Biofuels are gaining increased public, political and scientific attention, because high petroleum prices, greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels, food shortages and rising food prices, to name a few problems, are causing a host of issues related to world politics, national security, the economy and the environment.

First generation versus second-generation biofuels

First-generation biofuels are derived from sugar, starch, vegetable oil, or animal fats-products that are part of the food chain for animals and humans-and use conventional technology such as fermentation (e.g., corn or sugar cane) to produce ethanol or pressing (e.g., seeds, other oil-bearing fruits or plants) to produce oils. However, as the world's population has continued to grow, the use of food-related feedstocks for producing biofuels has been blamed for diverting food resources away from the food chain and contributing to food shortages and rising food prices.Second generation biofuels are made from non-food feedstocks such as plants and grasses, as well as agricultural waste, and are therefore considered a preferred alternative for producing biofuels. These non-food sources of biomass offer a solution that addresses political and environmental issues and also avoids the issues of food shortages and rising food prices. Second-generation biofuels use biomass-to-liquid technology to convert cellulose and hemicellulose, the fibrous material that makes up the bulk of most plant matter, into cellulosic biofuels such as cellulosic ethanol.

From a land-use perspective, second-generation feedstocks are lauded for growing well on land that wouldn't support food crops.